My collaborator and I are not on the list!

Alas!

But there are about half a dozen really cool ones HERE.

I particularly like Jhannes Oppermann's Walk Among the Dead, Hi by Jenn Martin and Todd Nicholas, and Estate by Patrick O'Leary. Babble, Dragon/Dragonslayer, Nos Morituri, and Paranormal Rescue Squad are also all interesting for one reason or another.

Walk Among the Dead is my pick for 1st place, as it has a very interesting mechanic that drives the game, which pushes uncertainty for the seeker player, competition for the rest, and makes a neat frame for moving the game along. The concept is also strong in that it makes a clear goal, an emotional motive for everyone, and a fun opposition.

Hi is my 2nd place pick. Here is a game with simple and concrete rules, but virtually no mechanics that come in play, so it is a very organic game. It simply gives each player one specific, and non-matching goal and path to get there. The interest is in seeing if the two paths end up converging, and therein is the story.

My 3rd place pick, is Estate. The prompted collaborative storytelling is not exceptionally innovative, but the concept that is wrapped around the mechanic is evocative.

I look forward to playing some of these when next I am on R&R!

Mostly about games and game design, with tangents into fairy tales, myths, weird horror, art, philosophy, politics, religion, history, and science. I may explore ideas that I don't believe in or agree with. Trigger warnings will not be given, nor ideas assured of being unquestioned... but respect for persons will. Grown up life is not safe, and adventures worth having demand risking the uncomfortable and unknown.

29 April, 2016

21 April, 2016

Willing Suspension of Disbelief

I am inclined to be a strong advocate of verisimilitude in art, by which I mean, that good art has to be believable even if it is about super heroes, or dragons. It vexes me for instance, when people discussing even so trivial a matter as a game world say, "the magic can be whatever we want it to be!" with no care as to what it is about or what it means. The "magic", is whatever the conceit of the fiction is, whether it has to do with fantasy wizards, or pseudo-science zombie apocalypse, etc.

On the one hand, they are quite right. As a matter of entertainment, you can do whatever makes you giggle. And there is nothing wrong with that. It is just a game after all, and (with rare exceptions) it does not provide you with food to eat, or clothes to keep out the cold, and all your fictions are so many paper leaves that will never love you back. Games are certainly trivial in that regard.

On the other hand, I keep recalling something about games as art that Jenova Chen (founder of That Game Company) said. Writing in his grad thesis, he reveals that it was a disturbing fact that as he got older, he found the (video) games he loved so much as a child to be less emotionally satisfying the older he got. He wanted to find ways to make them more emotionally compelling. He wanted to deepen the experience to be something that could be satisfying to adults as well. I would agree. For me as well, (tabletop) games provided a large part of my social grounding growing up, and I would add, a fair amount of grounding for my intellectual development as well. I'm not sure that I would have been so interested now in the history of the early twentieth century had I not first discovered Call of Cthulhu, and began to wonder more about the world that these cryptic terrors inhabited, for I had been exclusively steeped in pseudo medievalist fantasy games prior to that.

So I came across this interesting quote by the scintillating Mr. Aristotle in The Poetics:

"With respect to the requirement of art, the probable impossible is always preferable to the improbable possible."

He is talking about the use of possibilities and probabilities in fiction (more precisely in drama) mattering in evaluating the quality of the art (and I wondered if Theater History I would ever be useful!). In other words, dramatically satisfying fiction must be bolted to things that are believable to the human experience. Another way to look at it, is that the most convincing lies are 9/10 true. Zombies? Fine. Dragons? OK. Light speed space ships? Great. Verisimilitude must still have people that behave like people are actually known to do when confronted with dead things, gigantic scaly predators, and in a vast, empty expanse inimical to human life.

Mitigating the unlikelihood does not change this rule; it merely means that you have added subjective misunderstandings to the characters, but not to the objective "reality" of the fiction.

It has been years since I read Poetics, and I forgot that I'd read this, but I cannot recommend enough the reading of this book for narrativist minded games because of gems like this.

On the one hand, they are quite right. As a matter of entertainment, you can do whatever makes you giggle. And there is nothing wrong with that. It is just a game after all, and (with rare exceptions) it does not provide you with food to eat, or clothes to keep out the cold, and all your fictions are so many paper leaves that will never love you back. Games are certainly trivial in that regard.

On the other hand, I keep recalling something about games as art that Jenova Chen (founder of That Game Company) said. Writing in his grad thesis, he reveals that it was a disturbing fact that as he got older, he found the (video) games he loved so much as a child to be less emotionally satisfying the older he got. He wanted to find ways to make them more emotionally compelling. He wanted to deepen the experience to be something that could be satisfying to adults as well. I would agree. For me as well, (tabletop) games provided a large part of my social grounding growing up, and I would add, a fair amount of grounding for my intellectual development as well. I'm not sure that I would have been so interested now in the history of the early twentieth century had I not first discovered Call of Cthulhu, and began to wonder more about the world that these cryptic terrors inhabited, for I had been exclusively steeped in pseudo medievalist fantasy games prior to that.

So I came across this interesting quote by the scintillating Mr. Aristotle in The Poetics:

"With respect to the requirement of art, the probable impossible is always preferable to the improbable possible."

He is talking about the use of possibilities and probabilities in fiction (more precisely in drama) mattering in evaluating the quality of the art (and I wondered if Theater History I would ever be useful!). In other words, dramatically satisfying fiction must be bolted to things that are believable to the human experience. Another way to look at it, is that the most convincing lies are 9/10 true. Zombies? Fine. Dragons? OK. Light speed space ships? Great. Verisimilitude must still have people that behave like people are actually known to do when confronted with dead things, gigantic scaly predators, and in a vast, empty expanse inimical to human life.

Mitigating the unlikelihood does not change this rule; it merely means that you have added subjective misunderstandings to the characters, but not to the objective "reality" of the fiction.

It has been years since I read Poetics, and I forgot that I'd read this, but I cannot recommend enough the reading of this book for narrativist minded games because of gems like this.

19 April, 2016

Design Journal III: Markets and Flexible Economy in Fate

This has been another one of the tough nuts to crack in my design thinking.

The problem, is that Fate is a narrative and story oriented game. It is about people's choices more than it is about the crunchy bits of simulating physics or maths. On the other hand, economies and markets are entities of many parts and can be very complex indeed.

Part of what makes stories of clever traders, tricky fixers, and cunning grifters interesting, is that there is enough of a tip of the hat to these entities to the audience that they can vicariously feel clever too when the score is made honestly or otherwise. Even so simple a scene as THIS is interesting because of the details. Now the scale of the political game I have in mind is quite a bit larger, but through the faces of the player state, this kind of trading should be possible. Though there are few films that tell the stories, much of my interest in the history of trade and virtually all my interest in economics has to do with the constellation of mad, daring, world spanning adventures, schemes, and adventurers who at the end of the day just wanted to make a buck. The clever trading may not be the meat of the story, but it is the culmination. But then too, is the gamist satisfaction of "winning" in a way that directly supports the narrative. This is not a market simulation, but it should have enough complexity to make daring a journey half way round the world to bargain for a shipload of cheap goods that can be sold for a fortune back home.

My favorite part of the board game version of Civilization, was not the tech cards or the war part; it was blind trading three cards for three, two of which had to be truthful. Skins for dye... gold for wheat. Trading is a fun side business to raiding in Sid Meyer's Pirates! too. Several of my favorite non-fiction books are histories of trade... Nathaniel's Nutmeg, Scents of Eden, The Devil's Cup. The idea of a ship of adventurers looking to make a king's ransom with one big score leading to a war from a rival nation that ends in a peace treaty that grants an island territory on the opposite side of the planet... is just too crazy not to be ripe for fun. HERE, and HERE we can learn about Port Royal, a city chock full of murder hobos, a veritable Babylon of the West, in which the continuous fencing and resale of cargo to (more) legitimate merchants (for a commission) is a setting in which some level of mechanical detail beyond a single die roll to support the narrative might be in order. There should be some way beyond mere hand-waving to get some fun out of this kind of story focus.

So, I have two levels of resolution that I'm looking at. One is a much simpler Fate style challenge mechanic that can make less important trade, or more uninterested players move smoothly past trade to play in which ever ring of the political circus game they prefer. But I have been racking my brains trying to figure out how to explode this into a satisfactory fractal that has the right level of granularity to feel like a live, dynamic market economy, but still not get outside of the Fate play space.

I think the editing process for the 200 Word RPG contest kick-started my designer brain again, and I had an epiphany this afternoon.

Ultimately, it goes back to economics 101... Supply and Demand. I will have to expand a little more on the acquisition of resources later, but the core of the exploded, Fate fractal market starts with goods. There has to be a quick way to get an idea of some relative value of goods in order to give trading some verisimilitude. The simplified version will merely abstract this, and transactions will have no markers for the value or quantity of goods in trade; they will merely be narrative flavor like a created advantage or stunt. Transactions will be a contest of trade between the player merchant and the target market (PC or NPC). However, the fractal version determines the value of goods based on a quick calculation from three stats (R, F, L)

Raw Materials: - Common 1

- Uncommon 2

- Rare 3

Finished Goods: - Few materials 1

- Many materials 2

- Complex materials 3

Labor: - Basic skill 1

- Advanced skill 2

- Specialized skill 3

So for instance, Wheat is stated as R 1, F 0, L 1, for a (V) value of 2. Quick intuition can figure out that it is a raw commodity (seed), it is not a finished good, and it takes basic labor to put in the ground and to gather at harvest. There is obviously a fair amount of abstraction in the modeling of farming, but it gives a fair narrative model. Compare this to Iron ore (R 2, F 0, L 2, V=4) which can be turned into Iron ingots (R 2, F 1, L 2, V=5), that is used to make Armor (R 2, F 2, L 3, V=7) for values of 4, 5, and 7 respectively. Quick, easy, and can pretty much apply to anything that can be traded in scale. This gives a relative value between a load of Wheat at market, and a load of Armor. You could hand wave this if there was no narrative importance, but just the fact that one has more value than the other mechanically (though possibly not precisely as a simulation) gives 1) some relative narrative importance to which wagon matters more to the story of the guards, 2) a model for further market value that can also contribute to an abstract but still dynamic market for the merchants.

With that scratch-pad reckoning, that gets an idea of market value at the point of origin. But cost must also figure in getting it to market. At point of origin, silk in China was far cheaper than by the time it went thousands of miles west to Roman markets. The cost at every transfer port increased price. As such, zones are taken into account based on the difficulty of crossing from one zone into another zone. Essentially, you could travel a thousand miles across the Asian steppe in summer and it would be one zone, as there is little challenge between entering the zone and crossing into the next. Zones are measured by their final borders in other words; you can come in for free, but it costs to succeed in leaving (passing through). But, crossing the Tarim desert might count as a zone change calling for a +3 difficulty to pass through, and moving from the Tarim into and over the Tian Mountains along the Northern Silk Road is yet another zone change calling for a +4 difficulty before moving into the Steppes (easy enough... call it a +0 difficulty). So the basic distance mechanic calls for a +1 to the base value for every full +3 of difficulty in crossing zones to market.

So a load of silk in the Roman market at Antioch would be scratch pad priced thus:

Silk: R 1, F 1, L 2 (V=4) + shipping (quick estimate +4). It is an exotic item indeed, to Roman wives at a (C) cost of 7.

But while all of that deals more with the supply side of the market, there is also the demand side. This was also a tough part to crack, but I ultimately simplified it into a value based on how much the item is needed (or wanted enough to not distinguish a difference), and subtract the cost from that, dropping the integer to make a difficulty number to overcome by the merchant at sale.

Need: - Few need it 1

- Many need it 2

- Everybody 3

So again, in the case of Wheat (V 2) / (C 2) everybody needs it (N 3). N - C = -1, drop the integer, and you get 1, so the difficulty in selling wheat in a local market is +1. That means that the merchant has to overcome that difficulty to make a profit. Selling a load of Silk (V 7) imported from afar however, may prove harder. While most people would certainly like silk, probably you could judge it to have N 1. N - C = -6, drop integer and difficulty to sell it is +6 simply because it is exotic and expensive... most people simply can't pay the price.

Now the third ingredient mechanically, is to take into account a dynamic market. If you flood a market with wheat, the value of wheat is going to drop drastically as the supply outstrips the demand. Or if you can increase the supply of silk on the market, you can lower the price, and more people will be able to buy, which means that you can make up the profit over time. Since this is Fate though, we don't want to track a hundred commodities in real time, only the ones we are interested in for our story. So we need a way to put a lens on that. Thus, markets all have a stress boxes and consequences. In effect, the merchant player is attacking the market, and taking the stress as profit which goes back into replenishing that player's Resources stat, which I will discuss in another post. But if you attack the market too much, you put a narrative consequence which mechanically has enough detail to provide verisimilitude.

So in one last example, suppose your character sent a caravan east to bring back a load of silk to begin a trade monopoly so you could get filthy rich enough to buy the armies you need to keep your northern border safe from the stinky barbarians. The caravan does return from the daring venture (a whole separate series of sessions of story in play). Having cleverly used two create-an-advantage boosts (The Softest Clothes in the Empire, and Everyone Important in Tyre is Wearing Silk) to overcome the market in Antioch, ticks off two shifts of stress, and gives a consequence (Demand for Silk is Up) which allows an extra invoke the next time a silk shipment is in. Suppose another consequence came up though, and the market had so much silk that even the senior servants are wearing it? You might have the moderate consequence be Silk Demand Down. Anything important to the story about the market can be adequately, intuitively, and pretty realistically dealt with in this fashion.

So next, I need to deal a little more with Resources.

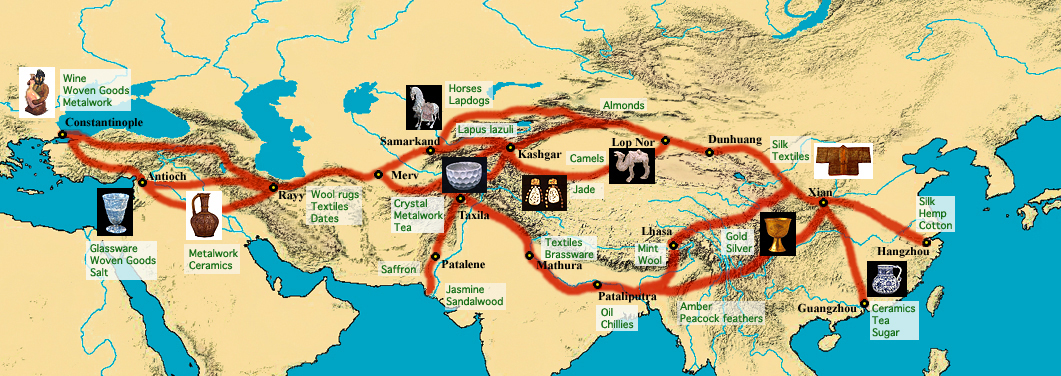

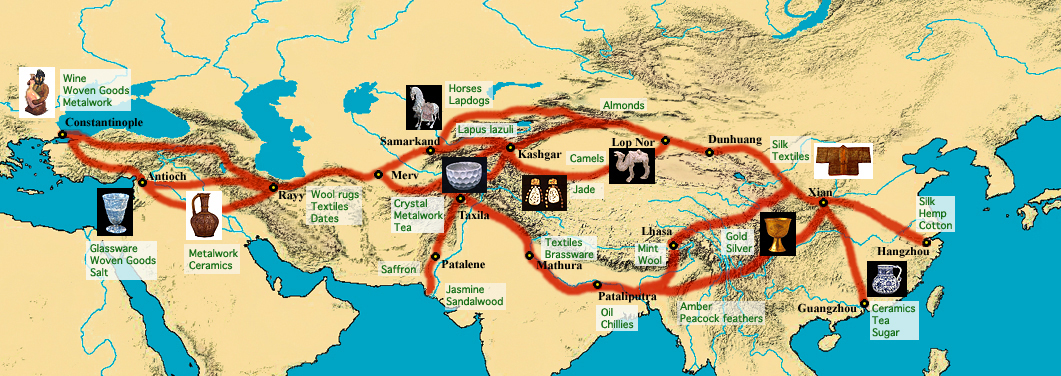

Here is a cool map that shows a little about the markets along the classic silk road. Too Cool!

The problem, is that Fate is a narrative and story oriented game. It is about people's choices more than it is about the crunchy bits of simulating physics or maths. On the other hand, economies and markets are entities of many parts and can be very complex indeed.

Part of what makes stories of clever traders, tricky fixers, and cunning grifters interesting, is that there is enough of a tip of the hat to these entities to the audience that they can vicariously feel clever too when the score is made honestly or otherwise. Even so simple a scene as THIS is interesting because of the details. Now the scale of the political game I have in mind is quite a bit larger, but through the faces of the player state, this kind of trading should be possible. Though there are few films that tell the stories, much of my interest in the history of trade and virtually all my interest in economics has to do with the constellation of mad, daring, world spanning adventures, schemes, and adventurers who at the end of the day just wanted to make a buck. The clever trading may not be the meat of the story, but it is the culmination. But then too, is the gamist satisfaction of "winning" in a way that directly supports the narrative. This is not a market simulation, but it should have enough complexity to make daring a journey half way round the world to bargain for a shipload of cheap goods that can be sold for a fortune back home.

My favorite part of the board game version of Civilization, was not the tech cards or the war part; it was blind trading three cards for three, two of which had to be truthful. Skins for dye... gold for wheat. Trading is a fun side business to raiding in Sid Meyer's Pirates! too. Several of my favorite non-fiction books are histories of trade... Nathaniel's Nutmeg, Scents of Eden, The Devil's Cup. The idea of a ship of adventurers looking to make a king's ransom with one big score leading to a war from a rival nation that ends in a peace treaty that grants an island territory on the opposite side of the planet... is just too crazy not to be ripe for fun. HERE, and HERE we can learn about Port Royal, a city chock full of murder hobos, a veritable Babylon of the West, in which the continuous fencing and resale of cargo to (more) legitimate merchants (for a commission) is a setting in which some level of mechanical detail beyond a single die roll to support the narrative might be in order. There should be some way beyond mere hand-waving to get some fun out of this kind of story focus.

So, I have two levels of resolution that I'm looking at. One is a much simpler Fate style challenge mechanic that can make less important trade, or more uninterested players move smoothly past trade to play in which ever ring of the political circus game they prefer. But I have been racking my brains trying to figure out how to explode this into a satisfactory fractal that has the right level of granularity to feel like a live, dynamic market economy, but still not get outside of the Fate play space.

I think the editing process for the 200 Word RPG contest kick-started my designer brain again, and I had an epiphany this afternoon.

Ultimately, it goes back to economics 101... Supply and Demand. I will have to expand a little more on the acquisition of resources later, but the core of the exploded, Fate fractal market starts with goods. There has to be a quick way to get an idea of some relative value of goods in order to give trading some verisimilitude. The simplified version will merely abstract this, and transactions will have no markers for the value or quantity of goods in trade; they will merely be narrative flavor like a created advantage or stunt. Transactions will be a contest of trade between the player merchant and the target market (PC or NPC). However, the fractal version determines the value of goods based on a quick calculation from three stats (R, F, L)

Raw Materials: - Common 1

- Uncommon 2

- Rare 3

Finished Goods: - Few materials 1

- Many materials 2

- Complex materials 3

Labor: - Basic skill 1

- Advanced skill 2

- Specialized skill 3

So for instance, Wheat is stated as R 1, F 0, L 1, for a (V) value of 2. Quick intuition can figure out that it is a raw commodity (seed), it is not a finished good, and it takes basic labor to put in the ground and to gather at harvest. There is obviously a fair amount of abstraction in the modeling of farming, but it gives a fair narrative model. Compare this to Iron ore (R 2, F 0, L 2, V=4) which can be turned into Iron ingots (R 2, F 1, L 2, V=5), that is used to make Armor (R 2, F 2, L 3, V=7) for values of 4, 5, and 7 respectively. Quick, easy, and can pretty much apply to anything that can be traded in scale. This gives a relative value between a load of Wheat at market, and a load of Armor. You could hand wave this if there was no narrative importance, but just the fact that one has more value than the other mechanically (though possibly not precisely as a simulation) gives 1) some relative narrative importance to which wagon matters more to the story of the guards, 2) a model for further market value that can also contribute to an abstract but still dynamic market for the merchants.

With that scratch-pad reckoning, that gets an idea of market value at the point of origin. But cost must also figure in getting it to market. At point of origin, silk in China was far cheaper than by the time it went thousands of miles west to Roman markets. The cost at every transfer port increased price. As such, zones are taken into account based on the difficulty of crossing from one zone into another zone. Essentially, you could travel a thousand miles across the Asian steppe in summer and it would be one zone, as there is little challenge between entering the zone and crossing into the next. Zones are measured by their final borders in other words; you can come in for free, but it costs to succeed in leaving (passing through). But, crossing the Tarim desert might count as a zone change calling for a +3 difficulty to pass through, and moving from the Tarim into and over the Tian Mountains along the Northern Silk Road is yet another zone change calling for a +4 difficulty before moving into the Steppes (easy enough... call it a +0 difficulty). So the basic distance mechanic calls for a +1 to the base value for every full +3 of difficulty in crossing zones to market.

So a load of silk in the Roman market at Antioch would be scratch pad priced thus:

Silk: R 1, F 1, L 2 (V=4) + shipping (quick estimate +4). It is an exotic item indeed, to Roman wives at a (C) cost of 7.

But while all of that deals more with the supply side of the market, there is also the demand side. This was also a tough part to crack, but I ultimately simplified it into a value based on how much the item is needed (or wanted enough to not distinguish a difference), and subtract the cost from that, dropping the integer to make a difficulty number to overcome by the merchant at sale.

Need: - Few need it 1

- Many need it 2

- Everybody 3

So again, in the case of Wheat (V 2) / (C 2) everybody needs it (N 3). N - C = -1, drop the integer, and you get 1, so the difficulty in selling wheat in a local market is +1. That means that the merchant has to overcome that difficulty to make a profit. Selling a load of Silk (V 7) imported from afar however, may prove harder. While most people would certainly like silk, probably you could judge it to have N 1. N - C = -6, drop integer and difficulty to sell it is +6 simply because it is exotic and expensive... most people simply can't pay the price.

Now the third ingredient mechanically, is to take into account a dynamic market. If you flood a market with wheat, the value of wheat is going to drop drastically as the supply outstrips the demand. Or if you can increase the supply of silk on the market, you can lower the price, and more people will be able to buy, which means that you can make up the profit over time. Since this is Fate though, we don't want to track a hundred commodities in real time, only the ones we are interested in for our story. So we need a way to put a lens on that. Thus, markets all have a stress boxes and consequences. In effect, the merchant player is attacking the market, and taking the stress as profit which goes back into replenishing that player's Resources stat, which I will discuss in another post. But if you attack the market too much, you put a narrative consequence which mechanically has enough detail to provide verisimilitude.

So in one last example, suppose your character sent a caravan east to bring back a load of silk to begin a trade monopoly so you could get filthy rich enough to buy the armies you need to keep your northern border safe from the stinky barbarians. The caravan does return from the daring venture (a whole separate series of sessions of story in play). Having cleverly used two create-an-advantage boosts (The Softest Clothes in the Empire, and Everyone Important in Tyre is Wearing Silk) to overcome the market in Antioch, ticks off two shifts of stress, and gives a consequence (Demand for Silk is Up) which allows an extra invoke the next time a silk shipment is in. Suppose another consequence came up though, and the market had so much silk that even the senior servants are wearing it? You might have the moderate consequence be Silk Demand Down. Anything important to the story about the market can be adequately, intuitively, and pretty realistically dealt with in this fashion.

So next, I need to deal a little more with Resources.

Here is a cool map that shows a little about the markets along the classic silk road. Too Cool!

17 April, 2016

Sci-Fi Tech and Humanity

I was looking at a couple articles today on BBC news and something that +Jacob Possin was thinking about on his G+ page. He was thinking about a semi-hard sci-fi setting and asking what kinds of tech others would think was important.

What occurred to me immediately, is that I'm at least as interested in how we are impacted as human beings by the technology we create as I am in just the mere capabilities of it as so often originally conceived. See, inventors mostly create new tech to solve a problem that they see. Often this has to do with a production or efficiency issue. However, what gets interesting (all too often in a distopian way) is how the tech gets used to manipulate and overcome other people in one fashion or another that has nothing to do with or the opposite intention of the original purpose. Facebook, the thing that was allegedly made to bring friends together, has also created new ways to anonymously gang up on and virtually assault people, sometimes to the point of their choice to suicide. It is also one of the largest data mining operations on the planet, and has been discovered manipulating data streams to bias political news to favor one side over the other based on whether the stories showed the party in a favorable or unfavorable light. Also, studies have shown that the highest users of Facebook have shown an overall decrease in happiness using it over time.

Not quite the invention it promised to be.

So the BBC story I was reading, also about Facebook, described the phenomenon in which as many as 30 million users who were now deceased, but still had active accounts, and sometimes, active data streams with continually updating content. The person was still "virtually alive" according to Facebook. One presumes that the content on the page over time continues to feed the profile picture of this person which generates the advertisements they get and the real junk mail and free promotional bait they get mailed to them.

The machine continues to seek for the ghost in the machine.

So what if your sci-fi Jovian moon colony, having to be self-sufficient for years at a time, and with asynchronous communication, has the latest communication and network tech. Say they have a real "network of things" in which virtually every machine of any kind from comm tech to basic construction tools on inventory all are chipped and part of the net. Suppose everybody is connected continuously to their version of Google Glass as a way of keeping records, gathering efficiency data, and providing a safety net. The Glass is likely to be a cyber implant somehow (possibly reversible possibly not) and is part of the network overseen by the Siri or Echo like AI that continues to keep the data and, like Siri or Echo, provide an internet voice to the database. The colony is sustainable enough that it is actually providing an economic return (be it ever so modest) to Homeworld, and thus has it's own modest economy. With 3D printing and aggressive, largely automated recycling factories on the moon, and the annual drone container ships bringing in new goods, there is a modest local version of Amazon mashed up with Makerbot catalogs. Because Siri tracks your social media data stream, it creates a virtual you, and a virtual profile of what you consume, so it auto orders and auto prints or delivers what it decides you want on a routine basis. Based on your profile, Siri auto-replies for you to those in your circles so you don't have to be interrupted in your personalized version of the latest Hollywood blockbuster (only a month old) which stars the CG star of your choice. "You" can like back effortlessly. Work at the colony goes on, happy, comfortable, productive...

Until the plague.

A mutated super virus that wipes everyone out in short order. As people die, their virtual profile continues to "live on", moderated and updated by Siri, continuing to have virtual dialogues with other profile users. As more die, fewer live posts feed the data stream, and their content skews the profiling algorithms, which eventually skews everyone's data stream living or dead, and thus their profile over time to some degree. But the auto conversation between virtual users continues. Siri does not care about contact... only input and ouput and data.

The moon colony continues to hum for years, though at a reduced rate, and the responses generated and resource shipments back to Homeworld become increasingly odd... repetative, sometimes non-sequitur, and in a schizophrenic fugue. When an investigating team eventually arrives over a decade later, what they find is a ghost planet, populated by the technologic undead specters of the past.

* * *

I continued to chew on this idea and had a thought experiment for a little sort-of world building game.

How does future tech versions of some modern or near future tech in the shadow of human vice change society?

So the players each take turns picking an item of future tech and these are listed down the right. Then everyone discusses each node with a cardinal sin, and they determine what society does with this.

For instance, custom organ printing. In the shadow of Envy, we might ask, first, is the printer a Sharper Image printer? Or a WalMart printer? Top dollar tissue or does it require a one year contract of anti-rejection drugs? This could be like the I-phone vs. free offer phone choice, with status being afforded to those who can pay.

Gluttony as discussed in classics does not exclusively refer to eating too much, but to consuming in excess. In the shadow of Gluttony, an organ upgrade addict is the pathological step beyond the piercing or plastic surgery addict. Or you could just go there, and call Gluttony an excessive desire to eat...

Greed easily dovetails with both the above if you are the salesman chasing the next commission selling the custom organ printers by preying on all the vices, vanities, fears and self-loathing that consume the buyers.

Lust, Pride, Sloth, and Wrath can undoubtedly be found overshadowing their own organ printers. In a world taken one step further from our reality TV, convenience consumer culture, "re-skinning" takes on a much more disturbing meaning if you can print the bone, cartilage, and skin to look like the latest Kardashian...

What occurred to me immediately, is that I'm at least as interested in how we are impacted as human beings by the technology we create as I am in just the mere capabilities of it as so often originally conceived. See, inventors mostly create new tech to solve a problem that they see. Often this has to do with a production or efficiency issue. However, what gets interesting (all too often in a distopian way) is how the tech gets used to manipulate and overcome other people in one fashion or another that has nothing to do with or the opposite intention of the original purpose. Facebook, the thing that was allegedly made to bring friends together, has also created new ways to anonymously gang up on and virtually assault people, sometimes to the point of their choice to suicide. It is also one of the largest data mining operations on the planet, and has been discovered manipulating data streams to bias political news to favor one side over the other based on whether the stories showed the party in a favorable or unfavorable light. Also, studies have shown that the highest users of Facebook have shown an overall decrease in happiness using it over time.

Not quite the invention it promised to be.

So the BBC story I was reading, also about Facebook, described the phenomenon in which as many as 30 million users who were now deceased, but still had active accounts, and sometimes, active data streams with continually updating content. The person was still "virtually alive" according to Facebook. One presumes that the content on the page over time continues to feed the profile picture of this person which generates the advertisements they get and the real junk mail and free promotional bait they get mailed to them.

The machine continues to seek for the ghost in the machine.

So what if your sci-fi Jovian moon colony, having to be self-sufficient for years at a time, and with asynchronous communication, has the latest communication and network tech. Say they have a real "network of things" in which virtually every machine of any kind from comm tech to basic construction tools on inventory all are chipped and part of the net. Suppose everybody is connected continuously to their version of Google Glass as a way of keeping records, gathering efficiency data, and providing a safety net. The Glass is likely to be a cyber implant somehow (possibly reversible possibly not) and is part of the network overseen by the Siri or Echo like AI that continues to keep the data and, like Siri or Echo, provide an internet voice to the database. The colony is sustainable enough that it is actually providing an economic return (be it ever so modest) to Homeworld, and thus has it's own modest economy. With 3D printing and aggressive, largely automated recycling factories on the moon, and the annual drone container ships bringing in new goods, there is a modest local version of Amazon mashed up with Makerbot catalogs. Because Siri tracks your social media data stream, it creates a virtual you, and a virtual profile of what you consume, so it auto orders and auto prints or delivers what it decides you want on a routine basis. Based on your profile, Siri auto-replies for you to those in your circles so you don't have to be interrupted in your personalized version of the latest Hollywood blockbuster (only a month old) which stars the CG star of your choice. "You" can like back effortlessly. Work at the colony goes on, happy, comfortable, productive...

Until the plague.

A mutated super virus that wipes everyone out in short order. As people die, their virtual profile continues to "live on", moderated and updated by Siri, continuing to have virtual dialogues with other profile users. As more die, fewer live posts feed the data stream, and their content skews the profiling algorithms, which eventually skews everyone's data stream living or dead, and thus their profile over time to some degree. But the auto conversation between virtual users continues. Siri does not care about contact... only input and ouput and data.

The moon colony continues to hum for years, though at a reduced rate, and the responses generated and resource shipments back to Homeworld become increasingly odd... repetative, sometimes non-sequitur, and in a schizophrenic fugue. When an investigating team eventually arrives over a decade later, what they find is a ghost planet, populated by the technologic undead specters of the past.

* * *

I continued to chew on this idea and had a thought experiment for a little sort-of world building game.

How does future tech versions of some modern or near future tech in the shadow of human vice change society?

So the players each take turns picking an item of future tech and these are listed down the right. Then everyone discusses each node with a cardinal sin, and they determine what society does with this.

For instance, custom organ printing. In the shadow of Envy, we might ask, first, is the printer a Sharper Image printer? Or a WalMart printer? Top dollar tissue or does it require a one year contract of anti-rejection drugs? This could be like the I-phone vs. free offer phone choice, with status being afforded to those who can pay.

Gluttony as discussed in classics does not exclusively refer to eating too much, but to consuming in excess. In the shadow of Gluttony, an organ upgrade addict is the pathological step beyond the piercing or plastic surgery addict. Or you could just go there, and call Gluttony an excessive desire to eat...

Greed easily dovetails with both the above if you are the salesman chasing the next commission selling the custom organ printers by preying on all the vices, vanities, fears and self-loathing that consume the buyers.

Lust, Pride, Sloth, and Wrath can undoubtedly be found overshadowing their own organ printers. In a world taken one step further from our reality TV, convenience consumer culture, "re-skinning" takes on a much more disturbing meaning if you can print the bone, cartilage, and skin to look like the latest Kardashian...

The Henchman - Submitted for the 200 Word RPG Challenge

So I'm running on about 4 hours of sleep at work today (coffee!... oh, beautiful coffee!). The first actual draft, v. 1.1 came in at ~550 words. I wrote in Notepad so I didn't have the word count showing as my editor is far too ready to stomp on my creative brain. That was a good thing. Then the editing process began.

I edited. Then I edited some more. I spent all day on my day off doing this, and still, down to the wire, I was at 220 words. In flew SuperWife to leap tall paragraphs, and punch out word count in a single bound. We shouted, we kvetched, I explained game design vocabulary, she complained, we collaborated, and here is the very brief version! (NOTE: this game would not have happened, at least on time as a contest submission, without her. Thanks B!)

I will post the original later for comparison.

Several things were ingredients in the final stew. Polaris was the first game I ever read in which the mechanics fed into the narrative and the PCs are assured death in the end. Becoming, is a game that comes close, with the mechanics feeding the narrative of how the PC is changed and what they sacrifice along the way, but the idea of a story about actual character death it turns out, can be just as interesting as a book or movie of the same idea. It is the Kobayshi Maru principle; how we face death is at least as important as how we face life. The notion of making a story about that is compelling.

Another idea that I wanted to play with, was the idea of what is under the face of a story. I love stories with strong face characters, and I won't deny the need for a strong face either in fiction or fact to a movement. The army that defeated Rommel may not have been nearly so effective had it not had George Patton as the face. We remember Patton because he led a victorious army... who was it that Rommel beat first? Unless you are a WW II history buff, you probably don't know. But the army, the men who crewed the tanks did the fighting, and sweating, and bleeding. They were the ones who died. They mattered. That was the second ingredient in the stew. What kind of story can a game tell about the henchmen that follow the face?

Then the other ingredients are the seasonings. While the first two elements form the core of the narrative idea side of the game, the other elements compose the mechanics that have to be married to the narrative. Good design marries mechanics that directly encourage the kind of play that you want the narrative to be about. So I thought about how to do that. I wanted it to be a collaborative game, because the henchmen are the people that back up the face, or they all fail. I also wanted there to be some uncertainty about the outcome to bring the fun and interest of tension to the game. And I wanted there to be some competitive element to push the players to excel as well. Castle Panic is a game that very effectively brings elements of cooperation and competition with uncertainty of outcome. I also thought about game theory and the Prisoner's Dilemma, in which tension comes of rational people trying to weigh self-interest and altruism and failure for everybody all at once. All of this fed into the otherwise simple mechanics for task resolution.

The final ingredient, was trying to find a very simple way of structuring it. I wanted to use a finer grained Hero's Journey a la Joseph Campbell, but settled on a basic three act structure.

Here it is!

Another idea that I wanted to play with, was the idea of what is under the face of a story. I love stories with strong face characters, and I won't deny the need for a strong face either in fiction or fact to a movement. The army that defeated Rommel may not have been nearly so effective had it not had George Patton as the face. We remember Patton because he led a victorious army... who was it that Rommel beat first? Unless you are a WW II history buff, you probably don't know. But the army, the men who crewed the tanks did the fighting, and sweating, and bleeding. They were the ones who died. They mattered. That was the second ingredient in the stew. What kind of story can a game tell about the henchmen that follow the face?

Then the other ingredients are the seasonings. While the first two elements form the core of the narrative idea side of the game, the other elements compose the mechanics that have to be married to the narrative. Good design marries mechanics that directly encourage the kind of play that you want the narrative to be about. So I thought about how to do that. I wanted it to be a collaborative game, because the henchmen are the people that back up the face, or they all fail. I also wanted there to be some uncertainty about the outcome to bring the fun and interest of tension to the game. And I wanted there to be some competitive element to push the players to excel as well. Castle Panic is a game that very effectively brings elements of cooperation and competition with uncertainty of outcome. I also thought about game theory and the Prisoner's Dilemma, in which tension comes of rational people trying to weigh self-interest and altruism and failure for everybody all at once. All of this fed into the otherwise simple mechanics for task resolution.

The final ingredient, was trying to find a very simple way of structuring it. I wanted to use a finer grained Hero's Journey a la Joseph Campbell, but settled on a basic three act structure.

Here it is!

HENCHMEN: The Game of the Daring Band that Follows (v 1.5)

Requirements: 4 Henchmen, 1 NP Hero, 4 index cards; 16 Light tokens, 20 Dark tokens, Crucible for Tokens, pencil.

Write name and how you serve the Hero.

ACT1: Four Scenes

Framer vividly describes scene and foreshadows the Dark (Omen, Rumor, Victim, Minion), annotating card. Everyone receives one Dark Token, including Hero.

Narrator then shares meaningful Bond with Hero; annotating card. Hero receives one Light Token. Other players may contribute up to two times during ACT1. One Light Token per share. Repeat until all Henchmen Frame, and Narrate.

ACT2: Four Scenes

1ST Framer ties foreshadowing from ACT1 and reveals Dark force and fateful Risk to overcome.

Everyone secretly puts 1-3 Tokens into the Crucible. Narrator pulls tokens one at at a time and narrates confronting Risk. Light Tokens aid victory, Dark Tokens - defeat.

If Dark Tokens outnumber Light, either sacrifice life and keep Dark Tokens as Glory, or retreat, passing Risk to another. If Light outnumbers Dark; defeat the risk. Can use Light Tokens in personal pile. Any Light Tokens gained pass to Hero. Repeat.

ACT3

Place Hero’s Tokens in Crucible. Take turns drawing one Token, and describe the Hero’s Glorious final confrontation. More Light = Heroic Victory. More Dark = Glorious Sacrifice.

Requirements: 4 Henchmen, 1 NP Hero, 4 index cards; 16 Light tokens, 20 Dark tokens, Crucible for Tokens, pencil.

Write name and how you serve the Hero.

ACT1: Four Scenes

Framer vividly describes scene and foreshadows the Dark (Omen, Rumor, Victim, Minion), annotating card. Everyone receives one Dark Token, including Hero.

Narrator then shares meaningful Bond with Hero; annotating card. Hero receives one Light Token. Other players may contribute up to two times during ACT1. One Light Token per share. Repeat until all Henchmen Frame, and Narrate.

ACT2: Four Scenes

1ST Framer ties foreshadowing from ACT1 and reveals Dark force and fateful Risk to overcome.

Everyone secretly puts 1-3 Tokens into the Crucible. Narrator pulls tokens one at at a time and narrates confronting Risk. Light Tokens aid victory, Dark Tokens - defeat.

If Dark Tokens outnumber Light, either sacrifice life and keep Dark Tokens as Glory, or retreat, passing Risk to another. If Light outnumbers Dark; defeat the risk. Can use Light Tokens in personal pile. Any Light Tokens gained pass to Hero. Repeat.

ACT3

Place Hero’s Tokens in Crucible. Take turns drawing one Token, and describe the Hero’s Glorious final confrontation. More Light = Heroic Victory. More Dark = Glorious Sacrifice.

one plus one

11 April, 2016

200 Word RPG Challenge

I am going to try to enter the 200 Word RPG Challenge (see here).

While looking at some of the judges, I found some interesting links from some far more experienced designers.

One was to a discussion on a psychology study put together by economists and finance people at MIT. They were studying merit based pay rewards for work, and discovered that counter-intuitive to conventional belief, these often don't work. The found (in brief) that for boring, basic, low-skill physical tasks, higher cash (an extrinsic reward) mitigated the low intrinsic-reward for the task. However, for even rudimentary higher engagement, higher skill, higher thought tasks, merit pay systems actually degraded task performance. See the studies HERE and HERE. Also, HERE is an interesting video about it. One curious study tested merit pay for giving blood, and found that in some cases, the higher cash reward degraded the interest in giving blood, but the choice of cash contributions to a charity by the blood bank increased the interest because a) the cash was either insufficient for the intrinsic unpleasantness of blood-loss, or b) too much to make the unpleasantness intrinsically valued. But giving to someone else in a more concrete way appealed to altruism which provided an intrinsic reward.

This study also suggests applications in game design. Still chewing on that...

While looking at some of the judges, I found some interesting links from some far more experienced designers.

One was to a discussion on a psychology study put together by economists and finance people at MIT. They were studying merit based pay rewards for work, and discovered that counter-intuitive to conventional belief, these often don't work. The found (in brief) that for boring, basic, low-skill physical tasks, higher cash (an extrinsic reward) mitigated the low intrinsic-reward for the task. However, for even rudimentary higher engagement, higher skill, higher thought tasks, merit pay systems actually degraded task performance. See the studies HERE and HERE. Also, HERE is an interesting video about it. One curious study tested merit pay for giving blood, and found that in some cases, the higher cash reward degraded the interest in giving blood, but the choice of cash contributions to a charity by the blood bank increased the interest because a) the cash was either insufficient for the intrinsic unpleasantness of blood-loss, or b) too much to make the unpleasantness intrinsically valued. But giving to someone else in a more concrete way appealed to altruism which provided an intrinsic reward.

This study also suggests applications in game design. Still chewing on that...

Why?: Part II

Why games in general, and role playing games in specific?

I am interested in games because I am very interested in:

- creativity

- building relationships

- solving puzzles

- play

- thinking about ideas

- stories

Playing games with a serious-fun frame of mind, allows us to both step outside of ourselves, and engage with ideas serious or whimsical in a more naked fashion. They may reveal something about ourselves to others, or reveal something about ourselves to us, but they allow us to inhabit a different mind-space.

Now I suppose that many more practical people don't see that, and when they see games they just think of the immediate result, which is something to the effect of "I just spent two hours playing and I have no more money in the bank, vegetables from the garden, or square feet of clean space in the house, so what good did that time have?"

I beg to differ. The result from games is not material, and the reward is not always immediately obvious. I will go so far as to say that not all game play has the same value; if I play a game of Candy Land with my wife, the value is going to be very low, but playing chess is a different story.

I think this has to do with how close the game can come to creating Flow which I alluded to in a previous post. There has to be the sweet spot in game play between challenge and competence, and the challenge must evolve with the players. A role playing game that is a railroad murder hobo grind is going to be far less likely to provide that Flow state than a game that explores what you are willing to sacrifice to succeed. That pushes into that territory that Jenova Chen talks about in which the game provides emotional satisfaction beyond simple excitement.

The value to the practical minded, is that it allows us to peek into the dusty corners of our minds in a way that painting the house or gardening don't. I don't deny the value of practical tasks either, and am quite of the mind that games should not be the most important or even a large percentage of our lives, but I think even the practical minded are impoverished by discounting the value of imaginative and creative play, no matter how old. With social play, comes relaxation, and with that the ability to step outside of ourselves, and with that the possibility of stepping into the head-space of others, and that takes and builds trust, and trust builds relationships. Games are not the only way to do this, but they are an ideal medium for carrying all those things.

I am interested in games because I am very interested in:

- creativity

- building relationships

- solving puzzles

- play

- thinking about ideas

- stories

Playing games with a serious-fun frame of mind, allows us to both step outside of ourselves, and engage with ideas serious or whimsical in a more naked fashion. They may reveal something about ourselves to others, or reveal something about ourselves to us, but they allow us to inhabit a different mind-space.

Now I suppose that many more practical people don't see that, and when they see games they just think of the immediate result, which is something to the effect of "I just spent two hours playing and I have no more money in the bank, vegetables from the garden, or square feet of clean space in the house, so what good did that time have?"

I beg to differ. The result from games is not material, and the reward is not always immediately obvious. I will go so far as to say that not all game play has the same value; if I play a game of Candy Land with my wife, the value is going to be very low, but playing chess is a different story.

I think this has to do with how close the game can come to creating Flow which I alluded to in a previous post. There has to be the sweet spot in game play between challenge and competence, and the challenge must evolve with the players. A role playing game that is a railroad murder hobo grind is going to be far less likely to provide that Flow state than a game that explores what you are willing to sacrifice to succeed. That pushes into that territory that Jenova Chen talks about in which the game provides emotional satisfaction beyond simple excitement.

The value to the practical minded, is that it allows us to peek into the dusty corners of our minds in a way that painting the house or gardening don't. I don't deny the value of practical tasks either, and am quite of the mind that games should not be the most important or even a large percentage of our lives, but I think even the practical minded are impoverished by discounting the value of imaginative and creative play, no matter how old. With social play, comes relaxation, and with that the ability to step outside of ourselves, and with that the possibility of stepping into the head-space of others, and that takes and builds trust, and trust builds relationships. Games are not the only way to do this, but they are an ideal medium for carrying all those things.

07 April, 2016

Politics of the Mob

Conscience is quelled by the approval of the masses.

Wickedness is made invisible by the complacence of peers.

Guilt is discarded by the indifference of leaders.

Righteousness is forgotten when self-interest is held sacrosanct.

This is how the banality of evil can come to wreck nations long before the bloodshed begins amidst the flames of revolt. Becoming used to some new idea does not make the idea right. Either it was right to begin with, or not... familiarity or comfort with it does not make it otherwise.

It rarely comes all at once, but by one compromise, after another. Those compromises become more and more common when actual Truth is discarded in favor of "my truth". There may be little practical difference between the ubiquitous human proclivity for justifying excuses for wickedness, but stepping over the line of excusing objective evil to the point that evil is a politically negotiable fiction does velocitize the avalanche cascading down the slope.

Whether we can agree to call these facts or not, history is rife with the repetition of these propositions in societies and civilizations. The plain truth, is that each new generation must relearn them, or suffer their horrors, and to learn at all means for the previous generation not to be lax in teaching.

I may write more about the increase of social consciousness in game design, and the ways in which I differ with them... but these principles are where I can agree with the notion that games can have be more than mere entertainment or distraction. If in playing out the role of a nation and it's interests, no matter what those interests are, and playing aggressively in that role, is it not possible that in addition to the entertainment of playing the game well, that the fiction may speak truth about us in fact?

That is what I want to try to get my head around in designing my political game.

Wickedness is made invisible by the complacence of peers.

Guilt is discarded by the indifference of leaders.

Righteousness is forgotten when self-interest is held sacrosanct.

This is how the banality of evil can come to wreck nations long before the bloodshed begins amidst the flames of revolt. Becoming used to some new idea does not make the idea right. Either it was right to begin with, or not... familiarity or comfort with it does not make it otherwise.

It rarely comes all at once, but by one compromise, after another. Those compromises become more and more common when actual Truth is discarded in favor of "my truth". There may be little practical difference between the ubiquitous human proclivity for justifying excuses for wickedness, but stepping over the line of excusing objective evil to the point that evil is a politically negotiable fiction does velocitize the avalanche cascading down the slope.

Whether we can agree to call these facts or not, history is rife with the repetition of these propositions in societies and civilizations. The plain truth, is that each new generation must relearn them, or suffer their horrors, and to learn at all means for the previous generation not to be lax in teaching.

I may write more about the increase of social consciousness in game design, and the ways in which I differ with them... but these principles are where I can agree with the notion that games can have be more than mere entertainment or distraction. If in playing out the role of a nation and it's interests, no matter what those interests are, and playing aggressively in that role, is it not possible that in addition to the entertainment of playing the game well, that the fiction may speak truth about us in fact?

That is what I want to try to get my head around in designing my political game.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)